Carbide, tungsten carbide, hard metal, cemented carbide, and many other registered trademarks are often used indifferently to indicate a very popular material for the production of tools.

To be precise, those terms are not exactly interchangeable.

Hard metal, or cemented carbide, refers to a class of materials consisting in carbide particles dispersed inside a metal matrix. In most cases, the carbide of choice is tungsten carbide but others carbide forming element can be added, such as tantalum (in the form of TaC) or titanium (in the form of TiC).

The metal matrix, often referred as “binder” (not to be confused with wax and polymers typically used in powder metallurgy) is usually cobalt, but nickel and chromium are also used. This matrix is acting as a “cement”, keeping together the carbide particles (hence the “cemented carbide” definition).

To form hard metal, carbide powders are milled with the metal binder to obtain a powder that is consolidated through pressing, extrusion or metal injection molding (MIM), followed by sintering.

In that sense, cemented carbide is not a metal but, more properly, a composite material.

If titanium carbide prevails in the composition instead of tungsten carbide, a different material called “cermet” is formed.

If the components are melted and alloyed instead of sintered, stellite is formed; a cobalt-chromium alloy containing tungsten and molybdenum.

Now that we have defined cemented carbide, let’s have a look more in detail at their production process, applications and how vacuum furnaces play an essential role in that respect.

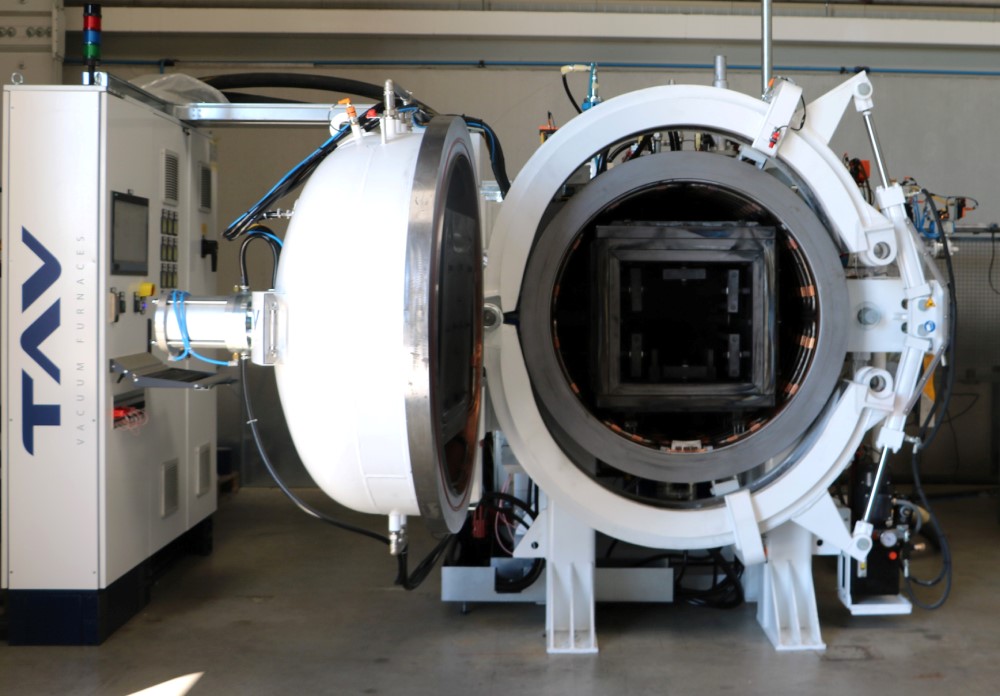

TAV VACUUM FURNACES HM Series - Sinter-HIP Furnace

Powders & Applications

To produce the starting powders, tungsten powder is carburized using different methods to obtain WC, then milled together with the metal binder and, possibly, with other carbides.

In their typical composition, those starting powders contain between 70% and 97% of tungsten carbides, while titanium and tantalum carbides might be present between 0,5% and 20%.

The cobalt content in commercial compounds varies between 3% and 25%. Other metal binders are sometimes preferred for specific applications; WC-Ni and WC-Ni-Cr systems for example are non-magnetic (as opposed to WC-Co) and are also preferred when high corrosion resistance is required.

To form the so called “green part” (a part made of powdered material, already shaped but not yet sintered) the starting powders are compacted using different techniques, depending on part size and complexity: cold and hot pressing, extrusion, or metal injection molding (MIM).

In all of the aforementioned techniques a fraction of wax or lubricant is added to allow sliding of the powder particles during pressing and guarantee the necessary strength to the green parts to be handled. This fraction can be very low, for hot pressing as an example, or significant, up to 7-8% in weight; that is the case for MIM.

Even though there is no universally accepted classification methods for cemented carbide, different composition are usually defined based on their application. According to ISO standards, cemented carbide for tools are divided into categories (K,P,M and, more recently, N,S,H) and subgroups called grades, denominated by increasing numbers according to the cobalt content. Each grade is specific for a certain workpiece material, machining method and working condition. To each grade a particular grain size is associated.

Grain size usually varies between 0,2 μm (nano) to 8 μm (extra-coarse).

Other than carbides composition, cobalt content and grain size are the main parameters affecting the mechanical properties of cemented carbide.

Generally speaking, toughness improves while hardness and wear resistance decrease with increasing cobalt content. On the other hand, for a certain cobalt level, hardness improves with decreasing WC grain size. Few examples of composition for some typical machining applications are provided in the next table.

|

ISO

Classification

|

Cobalt (wt %)

|

TiC (wt %)

|

TaC (wt %)

|

VC (wt %)

|

Cr (wt %)

|

Grain Size

|

Hardness

(HRA)

|

Grade

|

Typical Application

|

|

K01

|

5.5

|

/

|

0.7

|

/

|

/

|

Fine

|

92.4

|

Straight

|

Turning, Milling, Drilling Cast iron

|

|

K20

|

6

|

0.17

|

0.34

|

/

|

/

|

Fine

|

92.0

|

Straight

|

Turning, Milling, Drilling Cast iron

|

|

K30

|

11

|

0.4

|

0.8

|

/

|

/

|

Medium

|

89.7

|

Straight

|

Turning, Milling, Planing Cast iron

|

|

M10

|

6

|

/

|

/

|

0.2

|

0.3

|

Extra Fine

|

92.8

|

Micrograin

|

Turning, Milling, Drilling Super alloys

|

|

M25

|

10

|

/

|

/

|

0.3

|

0.5

|

Extra Fine

|

91.9

|

Micrograin

|

Turning, Milling, Drilling Super alloys

|

|

P15

|

5.5

|

3

|

4.5

|

/

|

/

|

Medium

|

91.4

|

Alloyed

|

Turning, Milling, Planing Steels

|

|

P30

|

10

|

6.5

|

11.4

|

/

|

/

|

Medium

|

91.2

|

Alloyed

|

Turning, Milling, Planing Steels

|

|

P45

|

11

|

5.5

|

3.5

|

/

|

/

|

Medium

|

90.5

|

Alloyed

|

Turning, Milling, Planing Steels

|

After powder compaction, the parts are ready to be sintered, which is necessary to consolidate the starting powder into parts with high density.

Dewaxing

The first step of the consolidation process is always dewaxing. As already mentioned, cemented carbide green parts contain a certain amount of wax/lubricant, often paraffin or PEG, that must be removed before heating the parts to the sintering temperature. Incomplete dewaxing before sintering can lead to the formation of entrapped gas porosity, coming from the evolution of wax vapours inside the parts, and carbon residuals.

It might be counterintuitive when talking about carbides, but an excess of free carbon inside the cemented carbide matrix is seriously detrimental for its properties. The tungsten-carbon-cobalt system in fact exists only when those elements have well defined proportions; too much carbon will form graphite (carbon porosities), too low carbon will form the undesirable η-phase. For that reason, controlling the dewaxing atmosphere and thermal profile is critical to ensure a complete removal of the binder at a suitable low temperature, below the “cracking” point, and avoiding both carburization and decarburization of the parts.

Depending on the wax chemical and physical properties, mainly melting point, boiling point and vapor pressure, several dewaxing methods can be applied, including both partial pressure dewaxing at few millibars or overpressure dewaxing, slightly above atmospheric pressure. In both cases, argon or hydrogen are used as process gas. For MIM parts, containing higher percentages and more complex wax-polymer systems, a solvent-dewaxing step is usually applied prior to thermal dewaxing.

Suitable wax trapping systems must be used to protect the vacuum pumps from contaminations, in the case of partial pressure dewaxing, or to condense most of the volatile organic compound before they can reach the afterburner at the furnace outlet, in the case of overpressure dewaxing. Moreover, a heated jacket can be fitted to pipe connecting the furnace to the wax trap, to prevent condensation of wax before the trap inlet and obstruction of the pipe in the long term.

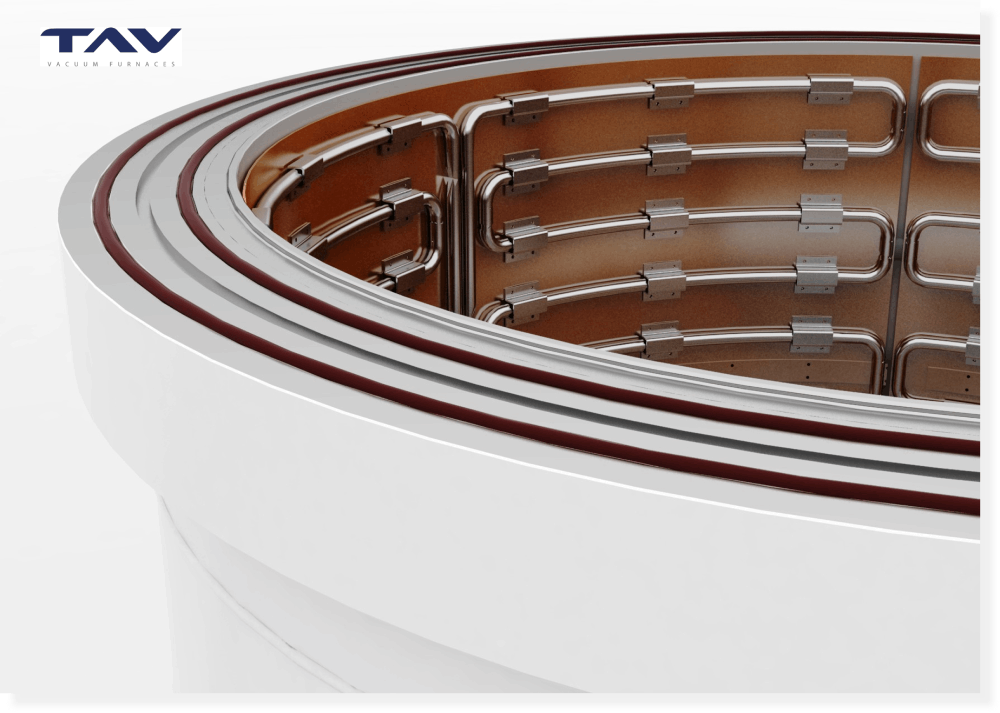

TAV VACUUM FURNACES Water Cooled Wax Trap

Furnaces operating with hydrogen overpressure requires additional systems and safeties, including an electrically or gas fired afterburner to prevent hydrogen accumulation in a confined area.

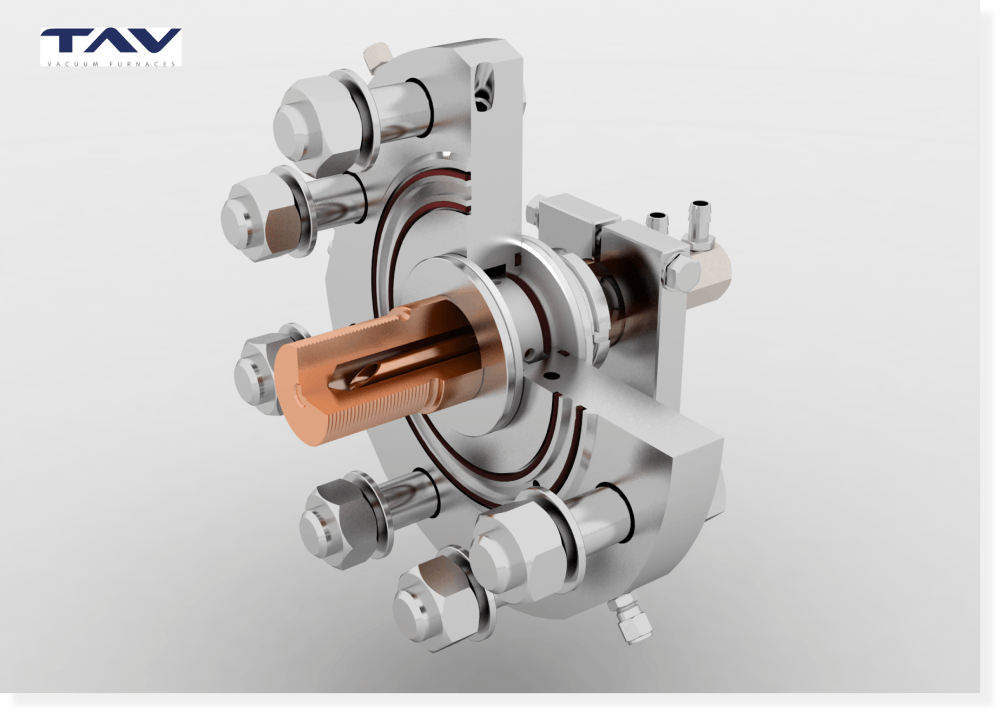

Additionally, at TAV VACUUM FURNACES we use our DST (Double Sealing Technology) on hydrogen furnaces to completely eliminate any possibility of leaks on all of the flanges, including the door. Finally, a safety PLC and redundant instrumentation ensures that all the relevant parameters are inside the operational safety level.

TAV VACUUM FURNACES DST (Double Sealing Technology)

Be sure not to miss the second part of the article, where we will discuss about vacuum sintering and sinter-HIP of cemented carbide, as well as the equipment dedicated to those processes!